Martial law is basically what it sounds like: an armed force taking over for law enforcement. In the United States, martial law means the U.S. military or National Guard is tasked to take over, typically in a limited region or part of the country.

There's a lot of legislation governing martial law in the U.S., because when it's used, things like "constitutional rights" tend to get tossed out the window. Most often, these are rights like gathering in groups, owning guns and protection from unreasonable searches and seizures. At least historically, the truth is that during martial law, the military officer in command can pretty much rule by decree and detain anyone for any reason.

For better or worse, martial law has been declared 68 times in the U.S. and its territories, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute. Natural disasters, riots and even Mormons have all resulted in the civilian government temporarily ceding its power to the military. Here are a few notable examples from throughout U.S. history.

In the last months of 1814, the British navy launched an offensive in the southern United States targeting West Florida and Louisiana. As the year came to a close, it was clear the British had their sights set on New Orleans. Standing in their way was Brevet Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson and his ragtag group of regulars, militiamen, slaves, pirates and Native American fighters.

Before all that (and actually after all that), Jackson declared martial law in the city. And also outside the city. Jackson turned New Orleans into a police state. He famously arrested a sitting Louisiana senator for publicly criticizing him. And when a federal judge demanded a writ of habeas corpus -- basically a demand for proof of wrongdoing -- Jackson arrested the judge, too.

Mormon leaders have twice declared martial law in areas they governed. The first time came in 1843, when Mormon founder Joseph Smith was accused of abusing his authority as mayor of Nauvoo, Illinois, after he beat the rap for allegedly trying to murder a former governor of Missouri.

Smith ordered the city to destroy a local paper critical of his office, so the citizens raised an army to capture him. Smith declared martial law and called out his own militia. The governor of Illinois then threatened to call in the state militia, but Smith escaped before it all went down.

By 1857, the Mormons had resettled in Utah, where some of their beliefs chafed against U.S. federal law. In response, Worst President Ever James Buchanan sent a large part of the U.S. Army to Utah to enforce federal law. After decades of persecution, the Mormons (understandably) flipped out, declared martial law and raised an army of their own.

Order was restored only after Mormon leader Brigham Young was replaced by Alfred Cumming, and the Mormons agreed to submit to federal authority and let the army into Utah. All Mormons were pardoned by the president.

President Abraham Lincoln's most dastardly deed (not a phrase you see every day) was the suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. Shortly after the South shelled Fort Sumter in April 1861, Lincoln allowed for the detention of civilians accused of being spies, saboteurs and other undesirables to the Union war effort, which meant pretty much anyone critical of the Union. Instead of facing good ol' American justice, the accused faced a military tribunal.

This didn't sit well with the Supreme Court, which ruled that as long as civilian courts within the justice system were able to try defendants, they still had the authority to do so. Military tribunals could only be used when the military was the only authority available. Ultimately, Lincoln's use of martial law resulted in a law known as the Posse Comitatus Act.

Labor unions may have a hard time getting started at places like Amazon, but that pales in comparison to what coal miners had to go through around the turn of the 20th century. For a group so critical to the U.S. economy, one might think things like a pay raise, some days not spent underground for 12 hours at a time and not inhaling arsenic dust would be an easy ask.

Nope. Corporate leaders would send in union busters to actively sabotage organization efforts. If that failed, the busters would just attack strikers. Strikers would fight back, sometimes taking it too far.

In 1892, striking miners in Idaho blew up a mill with too much nitroglycerin and destroyed nearby buildings. The governor declared martial law and sent in the National Guard to arrest 600 workers. Only a few of them were actually convicted of a crime.

When Colorado miners began a strike in 1914, it again erupted into violence. The governor sent in the National Guard to shut down the violence, which was successful -- for a while. Miners got violent again and a private army owned by the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company massacred more than a dozen people, including women and children. After the governor declared martial law, President Woodrow Wilson sent in federal troops. In 1917, martial law was again declared after union workers talked about a general strike during World War I.

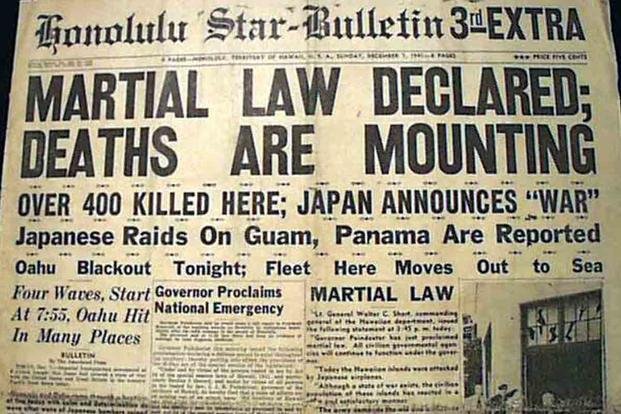

The same day the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, the territorial governor of Hawaii (which was not yet a state), declared martial law. His declaration would stand until October 1944 for fear of Japanese spies and saboteurs.

It may have seemed like the right call at the time, but according to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin newspaper, Gov. John Poindexter "surrendered" Hawaii to the U.S. military. The military used the occasion to force Hawaiians of Japanese descent off their land and to intern them in camps, 1,441 in all.

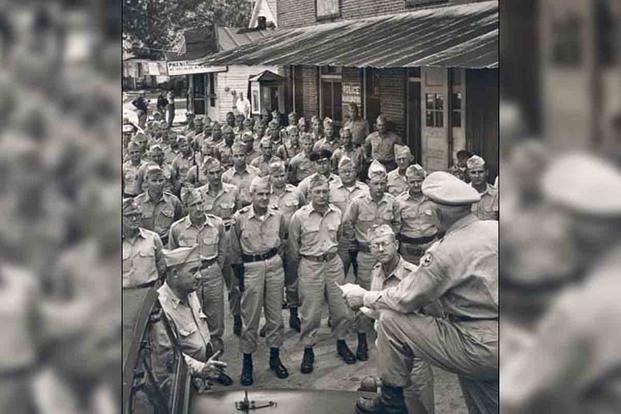

By now, we all know what happens when the production and sale of alcohol is banned in the United States: criminals start producing and selling alcohol. And they do it for a hefty profit. In a little town called Girard in Alabama, this cycle began in 1918 and quickly corrupted the town's law enforcement. When Girard merged with nearby Phenix City, the gangster corrupted Phenix City, too.

After 80,000 service members from nearby Fort Benning, Georgia, began patronizing the illegal watering holes, Phenix City became the "Wickedest City in America." After World War II, a wannabe district attorney ran his campaign on a platform of cleaning up the town. When he won, he was assassinated.

The governor of Alabama, realizing that local law enforcement was corrupted and useless, declared martial law. The Alabama National Guard used the authority of military rule to act in ways that would otherwise be unconstitutional. Weapons permits were invalidated, private clubs were raided and property seized. The entire underground economy was wiped out in less than a year.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Related Topics: Military History Law EnforcementBlake Stilwell is a former Air Force combat photographer with degrees and experience in Graphic Design, Television and Film, International Relations, Public Relations and Middle Eastern Affairs. Instead of using any of that, he (eventually) became a writer. His work has appeared in Recoil Magazine, Military Times, Coffee or Die, Skillset Magazine, and more. Blake is based in Ohio but is often found elsewhere. Read Full Bio

© Copyright 2024 Military.com. All rights reserved. This article may not be republished, rebroadcast, rewritten or otherwise distributed without written permission. To reprint or license this article or any content from Military.com, please submit your request here.